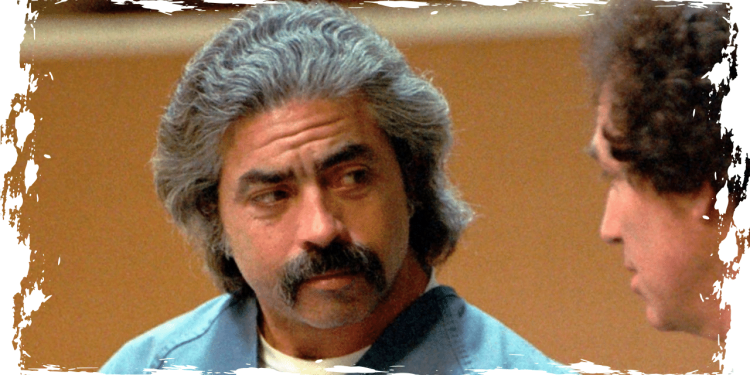

A California judge will decide whether to overturn Richard Allen Davis’s death sentence on Friday. Davis killed 12-year-old Polly Klaas in 1993 after taking her from her bedroom at knifepoint, a crime that stunned the nation.

In 1996, jurors found Davis guilty of first-degree murder as well as “special circumstances” such as kidnapping, burglary, robbery, and attempting lewd conduct on a minor. The jury sentenced Davis, who had a lengthy kidnapping and assault record dating back to the 1970s, to death.

In a February court filing, Davis’ attorneys argued that recent revisions in California sentencing legislation should vacate his death sentence. They also mentioned California’s existing prohibition on the death sentence. In 2019, California Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a moratorium on executions, calling the death penalty “a failure” that has discriminated against people who are mentally ill, black or brown, or cannot afford expensive legal representation. A future governor could amend the policy.

The Sonoma County District Attorney’s Office stated that Davis’ attorneys’ arguments are “nonsensical” and that the laws cited do not apply to Davis’ death sentence for Klaas’ murder.

Davis abducted Klaas from her bedroom in Petaluma, 40 miles (64 kilometers) north of San Francisco, in October 1993 and strangled her to death. That night, she and two friends had a slumber party while her mother slept in an adjacent room. Klaas’ disappearance prompted a worldwide search involving thousands of volunteers. Two months later, officers caught Davis and he guided them to the child’s remains, found in a shallow grave 50 miles (80 kilometers) north of her house in Sonoma County.

The case was a key driving force behind California’s implementation of the “three strikes” law in 1994, which mandated higher terms for repeat offenders. Both lawmakers and voters approved the idea.

California has not executed anyone since 2006, when Arnold Schwarzenegger was governor. In 2016, voters narrowly passed a ballot initiative to expedite the punishment, but no convicted inmate faced imminent execution.

Since the last execution, California’s death row population has expanded to include one out of every four condemned inmates in the United States.